Devices Too Smart for Our Own Good

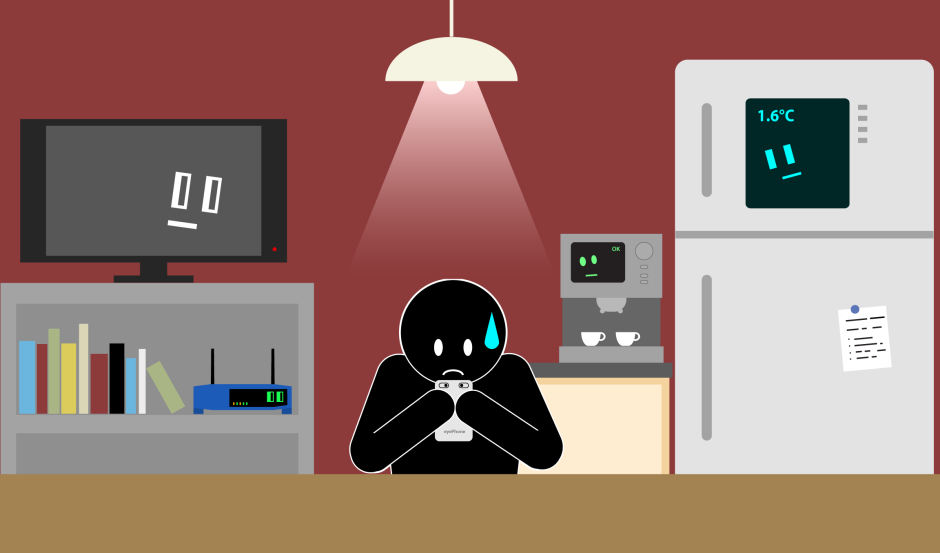

Who gets more value from smart devices: is it consumers, or is it companies, criminals, and spies?

Sometimes it seems like even the most cynical technophiles have one weakness: gadgets. We love playing with our shiny new smartphones, watching unboxing videos on YouTube, and getting deals on the latest headphones or dashcams. Even when our culture is not foisting consumerism upon us, it has subtly prepared us for the idea that the improvement of technology will continually, progressively make our lives better.

It’s difficult not to acknowledge that second point. We live on the cusp of an era where fleets of self-driving cars promise to offer the freedom of the open road to every person, with an overall reduction of accidents. Phones and speakers can respond verbally to our requests, as if we’re living in an episode of Star Trek. Indeed, it’s easy to get starry-eyed when so many of our devices have intelligence built into them.

But what’s the price of every device being so smart?

I’ve frequently argued that the combination of DRM with devices like printers, coffee makers, and even tractors brings about a status quo where the things we own are inherently disloyal to us. Much of our stuff now has firmware which makes it impossible – or even illegal – for us to repair our devices, and may even prevent those devices from functioning if we’re not using them exactly as the manufacturer intended. This grates against the expectation of many people that, once you buy something, you own that thing, and can do with it as you wish. Instead, it seems we’re entering a future where our own possessions are merely leased, and working against us.

This “disloyalty” isn’t limited to preventing repair and fair use. The advent of cloud computing means that computation often isn’t done by devices themselves. Rather, it’s easier for manufacturers to build devices which merely send queries to the manufacturer’s servers to be processed, with the results sent back to the device — virtual assistants like Siri and Alexa work this way. Not only does this mean our smart device becomes dumb as a stump the moment we lose Internet connectivity (or when the manufacturer’s servers go offline), but also that those same manufacturers are constantly collecting reams of data about each of us, every time we use our devices. So by merely using their devices, users have to trust that all the information being collected about their lives on manufacturers’ servers is both secure and private.

This is problematic for a few reasons.

Several manufacturers have unwittingly demonstrated that they’re not the most competent when it comes to handling private data or securing their devices against attacks. Canadian company Standard Innovationsettled a $4 million lawsuit this spring after it was revealed that the bluetooth-connected app of the We Vibe 4 Plus sex toy was collecting highly-specific information about device usage and sending it back to the company.

The We Vibe lawsuit is a pretty extreme, squicky example. That said, we live in an era where there are a lot of concerns with how companies are handling our data. We know that companies are selling our data to each other and compiling it to learn more about us, or to better ascertain how to sell us stuff, leading to an altogether creepy degree of personal data aggregation. At the same time, governments are working to get more and more access to the data that companies store about us, with less judicial oversight. This has the potential to create incredibly broad domestic surveillance, and enable detailed and intimate inspections of any given citizen’s private life.

An enormous population of Internet-connected devices — often with poor security — is also a huge boon for malicious hackers. Criminals leverage the ubiquity of IoT (“Internet of Things”) devices to create botnets: large, distributed networks of compromised devices under the hacker’s control, which can be used to attack websites or commit other crimes. Botnets can grow to be huge, and their power should not be underestimated. At the same time, government spy agencies like the CIA are concocting ways to use smart devices as listening or monitoring devices.

So, what’s a technophile to do?

I suspect that very few of us are willing to give up the convenience of our smartphones anytime soon. Many would probably argue that having a smartphone is a compromise between essential functionality and giving other parties access to our data.

That said, when we’re tempted to buy a new smart device, perhaps we should ask ourselves: to what degree will this thing truly improve my life, and to what degree is its manufacturer mining me for personal data? Perhaps that Internet-connected propane gauge or those bluetooth-connected, vibrating yoga pants (yes, they’re a real thing) don’t offer a marked improvement to your quality of life over their dumb counterparts; especially considering the price, both in terms of money and privacy.

Additional Reading:

I’m So Excited to Join a Botnet - some brief but excellent snark from Brian Feldman at Select All regarding his new sous-vide cooker.

The Internet of Things You Don’t Really Need - a thoughtful, in-depth analysis for the savvy, privacy-concerned consumer by Ian Bogost at The Atlantic.

Jesse Schooff is a veteran IT professional and technical communicator. As a volunteer blogger for OpenMedia he specializes in issues of privacy and information security. You can find more of his writing at geekman.ca

Take action now!

Take action now!

Sign up to be in the loop

Sign up to be in the loop

Donate to support our work

Donate to support our work