Governments Need to be Advocates for Infosec – Not Opponents

If the leaders of the democracies of the so called “Five Eyes” truly want to keep their citizens safe, the smartest thing that they can do is discuss how to reinforce encryption, and information security, rather than plotting to weaken it.

On Sunday, June 25th, Australia’s Attorney General announced in a press release that a priority point of discussion of the Five Eyes conference held in Ottawa would be “tackling encryption”, citing the ongoing global challenges of terrorism. In particular, the “involvement of industry in thwarting the encryption of terrorist messaging” has been one of the AG’s openly stated goals.

British Prime Minister Theresa May has also used the looming threat of terrorism as a lever for pushing an anti-encryption agenda, as did her colleague David Cameron before her. In Canada too, our federal police force, the RCMP, has become a vocal opponent of encryption. James Comey, former director of the U.S. FBI, made waves in the technology community back in 2016 when he demanded that Apple help compromise the security of their iPhone platform in order to assist in the investigation of the 2015 San Bernardino shootings.

Encryption is a versatile security technology. Not only does it keep our written communications private, it also secures our connections to our banks, keeps thieves from stealing our credit card data, keeps our tax returns safe when we transmit them to the government – to name only a few things. Encryption is also essential to critical IT infrastructure, not just of tech companies like Facebook, Google, and Microsoft, but also for any system which needs to keep malicious hackers out, such as electrical grids and hospitals. Nearly every technology we use and rely on every day is built on encrypted connections.

However, police and spies increasingly see encryption as an impediment to doing their jobs. Law enforcement is used to a certain way of doing things: find probable cause, obtain a warrant, and access a premises — sometimes forcibly — or wiretap a phone line to gather more evidence. So, somewhat justifiably, law enforcement officials feel that a warrant should allow them the means to forcibly “break into” the encrypted communications. Seems reasonable, right?

The problem is that encryption, as a technology, doesn’t work that way. Encryption obeys no laws except for the inflexible laws of mathematics and computer science. Unfortunately, it’s very difficult to explain precisely why without embarking on a long, complex explanation of technology and cryptography liable to tax the attention span of most people.

A better method of explanation is analogy, and example.

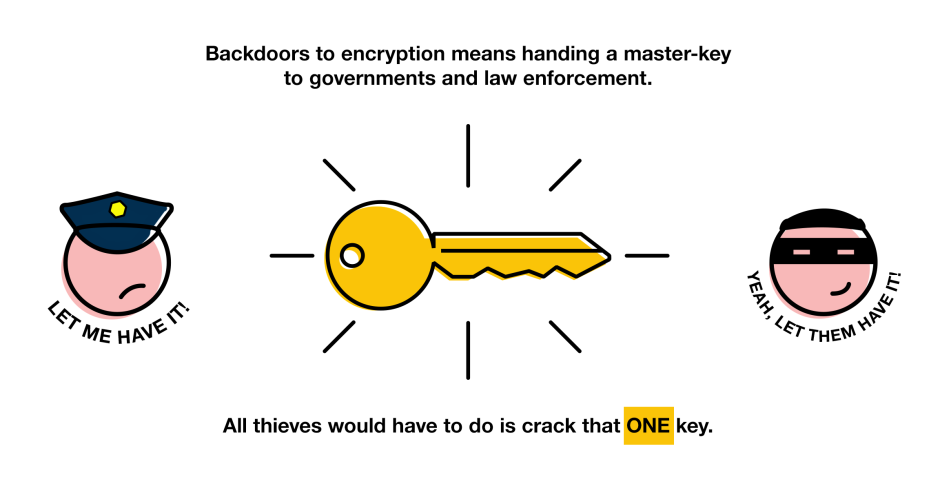

One of the suggestions that opponents of encryption frequently forward is the idea of “backdoors”. That is, the creation in any given encryption standard of a “master” key which can unlock any encrypted communications; a key which is known only to law enforcement.

After 9/11, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) in the United States began working with lock and luggage manufacturers to make sure that any lock could be opened by a TSA agent using a master key set. “TravelSentry”, as the standard is known, was meant to be a non-destructive way for TSA agents to open luggage for random inspections, without destroying locks or luggage in the process.

The problem is that when there’s only a few (or one) keys that open many different locks, it becomes relatively easy to figure out what the keys look like. Locksmiths would cite the task of reverse-engineering a lock as trivial. In 2015, photographs of a TSA agent’s keychain allowed a security researcher to 3D-print a replica of a TSA master key, essentially rendering many TravelSentry locks useless against any motivated thief.

While the technologies in comparison here are radically different, the core principle is the same (and one reviled by security experts): security through obscurity. That is, a system which is only secure as long as a big secret is well-kept by many. A TravelSentry lock is only secure until one person steals — or merely photographs — one of the many, MANY TravelSentry keys in existence. Likewise, encryption with backdoors built in is only secure until the master key is leaked, stolen, reverse-engineered, etc...

So encryption with a built-in “backdoor” is encryption with a built-in vulnerability. We live in an era where there’s a significant hack or security breach in the news nearly every other week. This is in part because criminal hackers are highly-sophisticated threats — motivated by profit or mere mischief to achieve their ends.

The global ransomware attacks of May, 2017 (known as “WannaCry”) gave us a small preview into the kind of chaos which can ensue when information security is undermined in the name of spies and law enforcement. Ransomware is leveraged by criminal hackers for profit, locking up an infected computer’s files until its owner pays a ransom to the hackers.

WannaCry spread rapidly, and caused chaos in the hospitals of England’s National Health Service, where staff were forced to turn away patients with non-life-threatening injuries, divert ambulances, and were unable to access some devices like MRI scanners. But one of the most infuriating things about the WannaCry attacks is that a lot of the blame can be laid at the feet of America’s National Security Agency, or NSA.

WannaCry — and its more recent relative Petya — were made possible by a critical bug first discovered in Windows systems by hackers at the NSA. One of the many revelations of WikiLeaks’ release of CIA documents earlier this year was that America’s federal spies and police hoard zero-day bugs (In IT security, security bugs are categorized by the number of days since they’ve been made public. Thus, an undisclosed bug is a “zero-day”). Even the DEA has been getting in on the game of zero-day hoards.

But this kind of behaviour endangers the public, because keeping bugs secret means that compromised systems are being used in the wild by ordinary citizens, by critical infrastructure (like hospitals), and even by governments. A bug discovered by the NSA might also have been discovered independently by criminals or terrorists. That’s why, under the Obama administration, it was a matter of policy that federal agencies would not be in the business of stockpiling bugs. Instead, it was mandated that security bugs would be submitted to technology companies so that they could be patched in a timely manner. It would seem that mandate was not respected.

By tearing down information security apparatuses in the name of “lawful access”, police, spies, and governments argue that they’re helping to defend the citizens and nations with whom they’re charged with the protecting. In fact, they’re doing the opposite. The discipline of computer science is a binary universe. Software is either ostensibly secure, or it’s insecure. Encryption either works, or it doesn’t work. There are no “backdoors for the good guys” because machines don’t understand the difference between the police and a criminal, only the difference between those who have access, and those who don’t.

Backdooring encryption, hoarding dangerous zero-day bugs, and other ostensibly well-intentioned efforts which undermine IT security, place everyone at risk. It places us at risk from terrorists, from criminals, and from other nations which might seek to undermine our sovereignty through hacking and subterfuge.

But perhaps the most damning argument about legally-mandated backdoors is that they won’t stop terrorism. In order to be effective, lawmakers would need to have jurisdiction over all software everywhere. What’s to stop a terrorist in Britain from installing an encrypted messaging app made by hackers on the darknet? Or which was created in Russia, or India, or in South America? Furthermore, investigation of the 2015 Paris attacks showed that the terrorists involved didn’t even use encryption, they used pre-paid “burner” phones. Should we ban cell phones too?

While backdoors will ultimately fail to prevent terrorism, they place everyone and everything else at hugely elevated risk of being hacked. The great magic of the Internet is that it allows a connected person or computer anywhere in the world to communicate with a connected person or computer anywhere else in the world. But that same magic requires that we have strict information security in place to protect ourselves from the many different people who would spy on us, steal from us, or otherwise do us harm.

It is for all these reasons — and for the equally-important protection of citizens’ private data from mass surveillance — that a group of European Union lawmakers has proposed legislation banning encryption backdoors. This is a first step in the right direction, but more work needs to be done to protect and bolster information security, in a world that has become so dependant on technology and the internet.

If the leaders of the democracies of the so called “Five Eyes” truly want to keep their citizens safe, the smartest thing that they can do is discuss how to reinforce encryption, and information security, rather than plotting to weaken it.

Take action now!

Take action now!

Sign up to be in the loop

Sign up to be in the loop

Donate to support our work

Donate to support our work