Will Bill C-11 #FixPrivacy in Canada or make it worse?

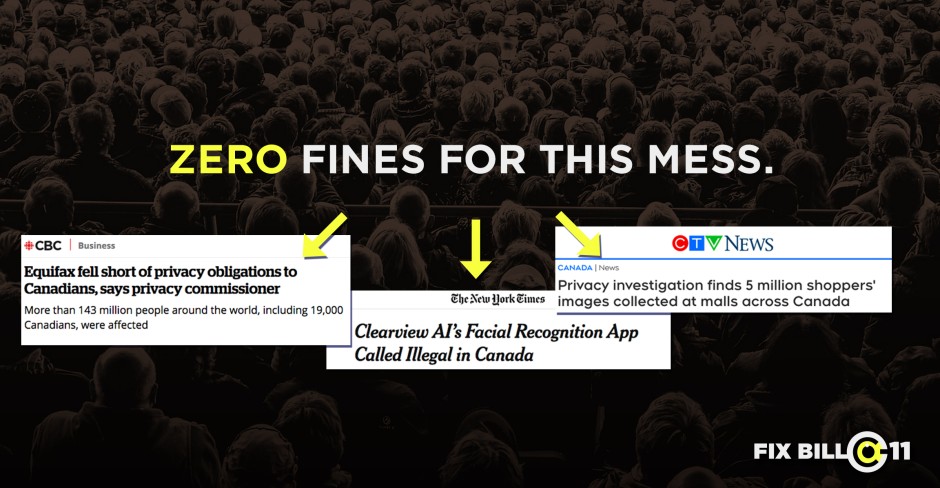

We were told that Bill C-11 would introduce huge fines for privacy violations. We put it to the test and it completely fails.

When introducing Bill C-11 last November, former Minister Navdeep Bains boasted that Canada would soon have the highest fines for privacy violations of any country in the G7. This would have been big news if it were true, but right away there were signs that the government didn’t want Bill C-11 to be closely scrutinized. The announcement came before the text of the Bill was released, and a press conference was held before journalists had the opportunity to read or review the Bill. As experts reviewed the Bill over the months since the announcement was made, the luster of the Bill has begun to fade. After all, the highest fines for privacy violations in the world won’t do a thing to defend our rights if they’re not widely applied.

So what would C-11 actually do for the privacy violations we’ve seen in Canada? To find out, we put the new fines to the test with several of the highest profile incidents investigated by the Privacy Commissioner of Canada over the last few years.

When it comes to privacy, its most basic legal premise is consent. In order for an organization to use your personal information, they’re first required to ask for your permission. Without this, privacy falls apart. We examined cases that involved clear violations of the consent provisions contained in Canada’s current private sector privacy laws, PIPEDA, and have analogous provisions in the proposed legislation, Bill C-11.

Despite Canadian laws being plainly broken in each case, none of these companies would face fines under Bill C-11 for what are obvious and clear consent violations. This is the case no matter how egregious the offence might be, and no matter how high the fines could be.

There’s a pretty simple reason for this. Bill C-11 restricts finable offences related to consent violations to two narrow areas:

- Fines for companies that force a person to give more personal information than necessary in order to receive a product or service;

- Fines for companies that obtain consent through deception.

But as you’ll see, the more basic consent violations outlined below can be more prominent and dangerous than these two limited infractions.

And here’s our bottom line: Unless the loopholes in C-11 are thoroughly fixed, and due concern for consent and human rights added, the fines introduced by Bill C-11 won’t go nearly far enough to protect the privacy of Canadians.

Clearview AI: Is the mass, indiscriminate, non-consensual surveillance of millions of Canadians a finable offence?

In early February of 2021, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, along with Provincial counterparts from British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec, released the findings of their joint investigation into the facial recognition company Clearview AI. This company had illegally harvested more than three billion images of people’s faces from websites on the Internet. It then created a database based on these stolen images, and provided access to 48 organizations across Canada, including law enforcement and private companies, as well as hundreds more in the United States, and more still around the world.

When an image of a face is uploaded into Clearview AI’s system by an end user, that image is compared to three billion other images, searching for potential matches in an attempt to identify the target in a process that undermines the privacy rights of everyone in the database. In effect, it creates a mass surveillance system of everyone on the open web. If you have a publicly available image of your face on the Internet, then you are in that database.

The Commissioners determined that Clearview AI, in collecting these billions of images, had committed consent violations and broken Canadian law. Clearview had failed to obtain valid consent for the personal information that they collected, used, and disclosed, and used the images for purposes that a reasonable person would not consider appropriate in the circumstances. In other words, this means that if you shared a picture of yourself with your friends and family on social media, you would not expect that Clearview AI would take that image and make it available for the police to use when trying to identify suspects in a criminal investigation. Or, even more problematically, you certainly would not expect that would happen in the event that somebody else took a picture of you and shared it on social media.

What Clearview AI did is an obvious and clear violation of our privacy rights and that is exactly what the Commissioners determined. But under Bill C-11, would Clearview AI be meaningfully punished for their actions?.

Not at all. In fact, under Bill C-11, another company could come along and do exactly what Clearview AI did — steal all of our pictures from social media and other websites, and sell access to law enforcement — and they too would face no fines. This is because Bill C-11 narrowly defines what consent violations are punishable with fines. And this very clear and extreme example is not one of those that would be finable.

This cycle could go on and on forever with companies continuously profiting from our loss of privacy and facing no financial penalties under Bill C-11. So in this case, the Bill absolutely fails to protect the privacy of Canadians.

Equifax Canada: Is the non-consensual sharing of sensitive personal information with a foreign third-party a finable offence?

In April of 2019, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada released findings from their investigation into a breach of personal information that affected 147 million people globally, including an estimated 19,000 people in Canada. The incident affecting Canadians occurred after Equifax Canada, a credit reporting agency, transferred personal information to a third-party in the United States, which suffered the massive data breach. Breached information included social security numbers and other highly sensitive identifying information.

The Commissioner found that Equifax Canada had not received consent before transferring personal information to this third-party in the United States, and had therefore broken Canadian privacy law. Like with Clearview AI, this is a basic consent violation. Equifax Canada simply failed to ask people for permission to share their sensitive personal information with the third-party in a different jurisdiction, where they could offer no guarantees about how that information would be protected, and where it was ultimately breached.

Under Bill C-11, out of the two fines that are available for consent violations, this violation would not qualify for either. Once again, Bill C-11 would fail to protect the privacy of Canadians and would miss the opportunity to incentive other companies to enact practices that prevent this kind of incident from happening again.

Cadillac Fairview: Is secret biometric data collection a finable offence?

In late October of 2020, the Privacy of Canada, along with Provincial counterparts in British Columbia and Alberta, released the findings of their joint investigation into Cadillac Fairview, a company that owns and operates Canadian shopping malls. In some of these malls, the company installed hidden cameras in their information kiosks. The program was never publicly announced; the presence of these cameras was only discovered when one of the kiosks malfunctioned and displayed an error code that led to a member of the public taking it upon themselves to investigate.

These cameras filmed anyone near the kiosks and recorded and analyzed biometric information about them using a form of facial recognition technology. In particular, the company was interested in the ages and genders of people. The company posted no notices that these cameras were operating and relied on a sticker on the entrance doors to the mall that directed people to the customer service desk if they were interested in reading the privacy policy. Buried deep within this document, was information about what was occurring with the cameras hidden in the kiosks.

The Commissioner determined that this was an inadequate form of consent for such an invasive form of surveillance. Even more troubling, they found that should someone read that sticker on the entrance doors, make the trip to the customer service desk, and request the privacy policy, the representatives there were not equipped to provide it.

This is another example of a very clear and plain privacy violation centred around the concept of consent: A reasonable person entering a mall would not expect that hidden cameras would be surveilling them and making assessments about their age and gender and then recording this information. In fact, if this was known to be occurring at a mall, it would be reasonable to expect that some people would make the choice to shop somewhere else.

After the investigation, the company suspended the practice of using hidden cameras to surveil its guests, but made no guarantee to the Commissioners that it wouldn’t use the technology again, and didn’t concede that its practice of displaying a sticker on the entrance door that directed people towards a place that a privacy policy was said to exist was an inadequate form of consent.

No fine would have been available under C-11 to correct what many would agree is a clear privacy violation centred around the notion of consent, the use of facial recognition technology, and the collection, storage, and use of biometric information.

Aggregate IQ: Is mass data harvesting for the purpose of undermining democracy a finable offence?

In November of 2019, the Privacy Commissioner of Canada, along with the Information and Privacy Commissioner of BC, released their findings from their joint investigation into Aggregate IQ. This investigation stemmed from the Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal, where it was alleged that Aggregate IQ was operating as the Canadian arm of Cambridge Analytica—the company that had infamously used personal information taken from Facebook to influence voters in elections all around the world, sometimes actively discouraging participation in democracy.

This was quite a complex investigation and report of findings. Aggregate IQ was involved in political campaigns outside of Canada, and the Commissioners found that the company had committed consent violations in their work in the United Kingdom and the United States. What makes the investigation so complicated is that the company obtained sensitive information from a wide variety of different sources and used that information in many different ways.

In the case of the campaign from the United Kingdom, the company had worked on behalf of ‘Vote Leave’ in the leadup to the vote about whether to remain in the European Union. The Commissioners found that the company had disclosed personal information to Facebook in order to advertise and promote the campaign in ways that violated consent provisions in Canadian privacy law.

For the campaigns in the United States, the Commissioners found that Aggregate IQ had used personal information that had been illegally collected from Facebook, and was shared with the company through Cambridge Analytica.

So in each instance, Aggregate IQ was found to be either disclosing to, or using information that was collected by, Facebook in manners that violated the consent provisions of Canadian privacy law. Even though the personal information may have largely pertained to people in foreign jurisdictions, like the United Kingdom and the United States, the Commissioners found that Aggregate IQ was subject to Canadian privacy laws because it operated in Canada.

At this point, you won’t be surprised to learn that neither of these violations would receive a fine under Bill C-11. Once again, this is another high profile incident showing how Bill C-11 would fail to protect the privacy of Canadians because it doesn’t create significant deterrents — in the form of financial penalties — to deter private companies from breaking the law.

So what does Bill C-11 do when it comes to consent?

So you might be wondering, after reading about all the things C-11 won’t do when it comes to consent, what this Bill does do. The proposed legislation does introduce two finable offences related to consent violations. It also introduces a new exception to consent that could prove to be extremely problematic.

The first finable offence is for a company that makes a person consent to the collection of more personal information than necessary, in order to receive a product or service, a condition of receiving that service. So, for example, if an application on your phone for a game required you to provide your social insurance number in order to play the game, that would be a finable offence under the proposed laws.

The second finable offence is for consent obtained by deception. Bill C-11 would introduce a fine for a company that obtains consent by making false or misleading statements. For example, a company couldn’t present itself as a social media platform, while really taking the photos shared on it and using them to create a database of facial recognition images and then renting access to it to law enforcement.

But for companies that don’t seek to achieve consent at all? No fines. Outrageously, Bill C-11 as written incentivizes companies to not ask for consent at all, rather than to risk coercing a person into consenting through false or misleading statements, or through risking over collecting what is strictly necessary.

Most egregiously, in Bill C-11, a new exception to consent will be introduced, giving companies a new reason to not ask people for permission before collecting, using, or disclosing their personal information. Under the proposed legislation, companies that don’t have a direct relationship with a person will no longer be required to ask for consent.

The potential implications of this exception are incredibly broad. A company like Clearview AI could claim that they did not have a direct relationship with any of the people whose photos they harvested for their illegal database. Perhaps, in the case of Cadillac Fairview, a third-party company could be used to collect and analyze the biometric data they obtained through their hidden kiosk cameras because they could claim to be a company without a direct relationship with the people visiting the malls. Or Aggregate IQ could make the claim that they did not have a direct relationship with any of the people whose personal information they used to influence their voting behaviour because they received it from third parties, like Facebook and Cambridge Analytica.

So where do these case studies leave us? Without serious revisions, the possibilities for even greater privacy violations under Bill C-11 than we face today seem endless, and the fining mechanisms appear to be a failure when it comes to protecting Canadians. Enhancing the consent protections by expanding the finable violations to include all violations of consent, and removing the new consent exemption, would go a great distance to making this proposed legislation something that would actually protect the privacy of Canadians.

We’re speaking out to demand the government put consent at the centre of fixing C-11. To add your voice, click here.

Take action now!

Take action now!

Sign up to be in the loop

Sign up to be in the loop

Donate to support our work

Donate to support our work